Understanding the Intent of "All Men Are Created Equal"

Part 3: "...an expression of the American mind"

“…this was the object of the Declaration of Independ[e]nce. [N]ot to find out new principles, or new arguments, never before thought of, not merely to say things which had never been said before; but to place before mankind the common sense of the subject; [in?] terms so plain and firm as to command their assent, and to justify ourselves in the independ[e]nt stand we [were?] compelled to take. [N]either aiming at originality of principle or sentiment, nor yet copied from any particular and previous writing, it was intended to be an expression of the American mind, and to give to that expression the proper tone and spirit called for by the occasion.”

- Letter from Thomas Jefferson to Henry “Light-Horse Harry” Lee, May 8, 1825

The year is 1825. Thomas Jefferson is 83 years old, and although he doesn’t know when, he can undoubtedly sense his end is near.

After years of correspondence with John Adams discussing the meaning of the Revolution, he knows there’s one crucial final task remaining: clarifying for all time the intent of the Declaration of Independence. So he writes to his friend, and Revolutionary War hero and fellow Virginian, Henry Light-Horse Harry Lee.

And while Jefferson’s letter is clearly reflecting on the Declaration’s overall intent, there’s also historical evidence that strongly supports its application to the five all-important words this series of posts focuses on. Put simply, the question of whether Christian morality and Enlightenment principles required equality for all under the law was alive and well throughout the colonies, leading up to 1776.

It rang out in Boston’s newspapers and pulpits, as well as the state legislature.

It was the subject of sermons in Connecticut.

It was a lively debate in the Pennsylvania Quaker meeting houses and the state’s political arenas.

Even Virginian newspapers and the state’s House of Burgesses echoed with debate on what would become humanity’s essential question.

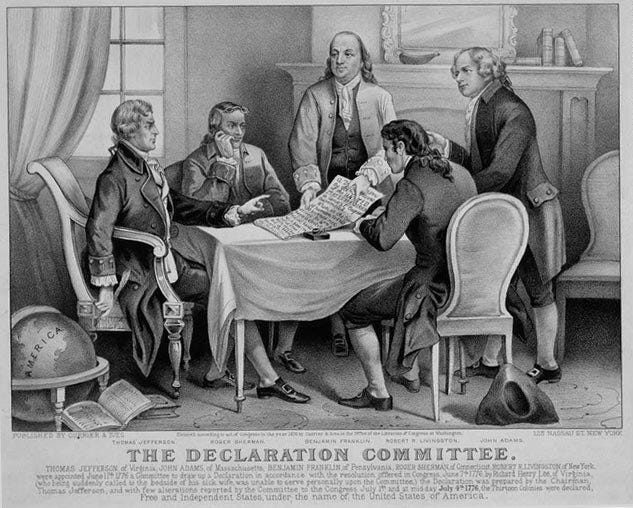

Prominent religious and political leaders in these states at the time answered in the affirmative, condemning slavery in various ways and articulating egalitarian and Lockean principles. It’s likely not a coincidence that John Adams (MA), Roger Sherman (CT), and Benjamin Franklin (PA) represented those states alongside Jefferson on the Declaration’s drafting committee.

However, it’s also important to understand that the antislavery perspective did not represent a consensus view. Many prominent colonists disagreed.

The plantation economies of South Carolina and Georgia were nearly entirely dependent on enslaved labor at the time of the Declaration. Little to no debate over the legal or moral legitimacy of slavery was possible.

In fact, even a proposal to free less than 5% of those enslaved in the two states to fight in the Revolution just three years later - promoted by South Carolinian John Laurens and passed by the 1779 Continental Congress - was viewed as a “dangerous and impolitic Step” by SC’s leaders.

There were also plenty of defenders of the institution in the north, particularly in New York.

So, although Jefferson’s words that “all men are created equal” were an accurate and accepted truth for those on the Declaration’s drafting committee and many of the colonists those men represented, the statement advanced a revolutionary principle for those in the Deep South, many in the northern and Mid-Atlantic colonies, and nearly all of the world. Indeed, America became the first nation in world history to have this principle of radical legal egalitarianism embedded in one of its founding documents.

This post will provide the details on the public sentiment in the states represented by those on the drafting Committee in the years leading up to the Declaration. Links to original sources are provided throughout. The post concludes by compiling the actions and events in an easy-to-reference chronological timeline not found anywhere else.

This summary is needed now more than ever, as certain historians with political agendas continue to peddle myopic, revisionist versions of American history that have misled an entire generation. In so doing, they’ve contributed to undermining the principles this nation was founded on.

It’s time to set the record straight.

Given its breadth, condensed nature, and uniqueness, this post is only for paid subscribers.

Thank you for considering supporting the work of the Great Americans Project.